For decades, if you wanted a continuous-wave ultraviolet-B laser, you had two terrible options: operate it in short pulses, or cool it to cryogenic temperatures. Neither is practical for most applications.

A team at Meijo University in Japan just eliminated both constraints. They've demonstrated the world's first room-temperature, continuous-wave UV-B semiconductor laser, and it runs on an inexpensive sapphire substrate. The research appears in Applied Physics Letters.

Let me explain why this is hard.

UV-B light (wavelengths around 280-315 nanometers) requires semiconductor materials with very high aluminum content—specifically, aluminum gallium nitride alloys. The more aluminum you add, the shorter the wavelength you can generate. Sounds simple, except aluminum-rich nitrides are notoriously difficult to grow without defects.

Those crystal defects act like potholes for electrons. They scatter charge carriers, generate heat, and prevent the sustained population inversion you need for continuous lasing. Previous UV-B lasers could only operate in pulsed mode (giving the material time to cool between pulses) or required liquid nitrogen cooling to suppress thermal effects.

The Meijo team solved this with several clever tricks:

First, they used a relaxed aluminum gallium nitride template—essentially pre-straining the crystal lattice to reduce defect formation while maintaining optical quality. Think of it like pre-stretching a canvas so it doesn't warp when you paint on it.

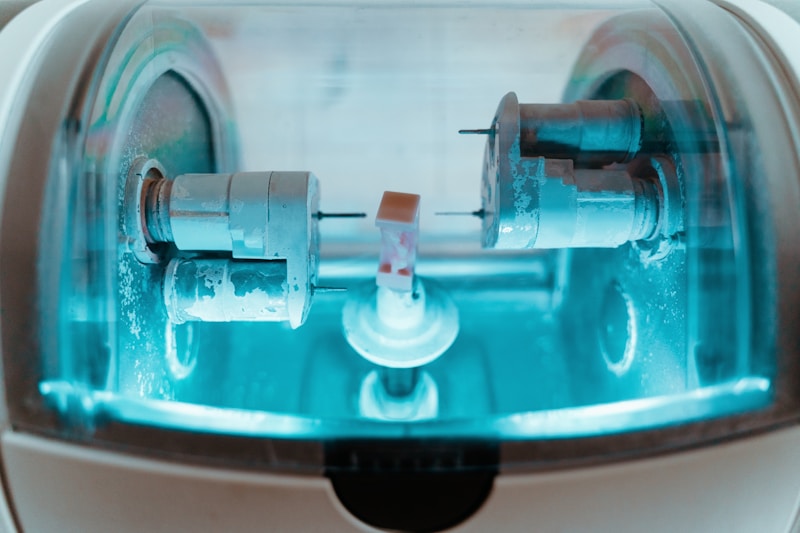

Second, they designed a refractive-index-guided ridge waveguide to confine light efficiently within the laser cavity, compensating for the material's naturally poor optical properties.

Third, they added high-reflectivity dielectric mirrors to enhance laser feedback, lowering the threshold current needed to achieve lasing.

Finally, junction-down mounting—flipping the chip upside down so the heat-generating junction sits directly against the heat sink.

The result: a laser emitting at 318 nanometers with a threshold current of 64 milliamps, operating continuously at room temperature. As Professor Motoaki Iwaya noted, "Continuous-wave operation at room temperature has been a long-standing goal for UV-B semiconductor lasers."

Now, applications. UV-B lasers enable medical phototherapy for skin conditions, high-resolution DNA sequencing, fluorescence microscopy, surface sterilization, and precision semiconductor lithography. Currently, most of these applications rely on bulky gas-discharge lasers (essentially fancy fluorescent tubes). Compact semiconductor lasers could replace them within five to ten years—if the technology scales.

And that's the caveat: this is a laboratory demonstration. The team achieved lasing, which is the hard part, but commercial viability requires improving efficiency, extending operating lifetime, and manufacturing at scale. Many promising laser breakthroughs have stumbled at that stage.

That said, the physics is elegant. And elegant physics has a tendency to find its way into the real world.

The universe doesn't care what we believe. Let's find out what's actually true.