A research team at the Department of Energy's Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility is developing technology that could transmute long-lived nuclear waste into shorter-lived isotopes — while generating electricity in the process.

The headline claim is striking: a 99.7% reduction in radioactive lifespan. More precisely, the technology could reduce storage requirements from approximately 100,000 years to just 300 years. Still a significant hazard period, but a dramatic improvement over geologic timescales.

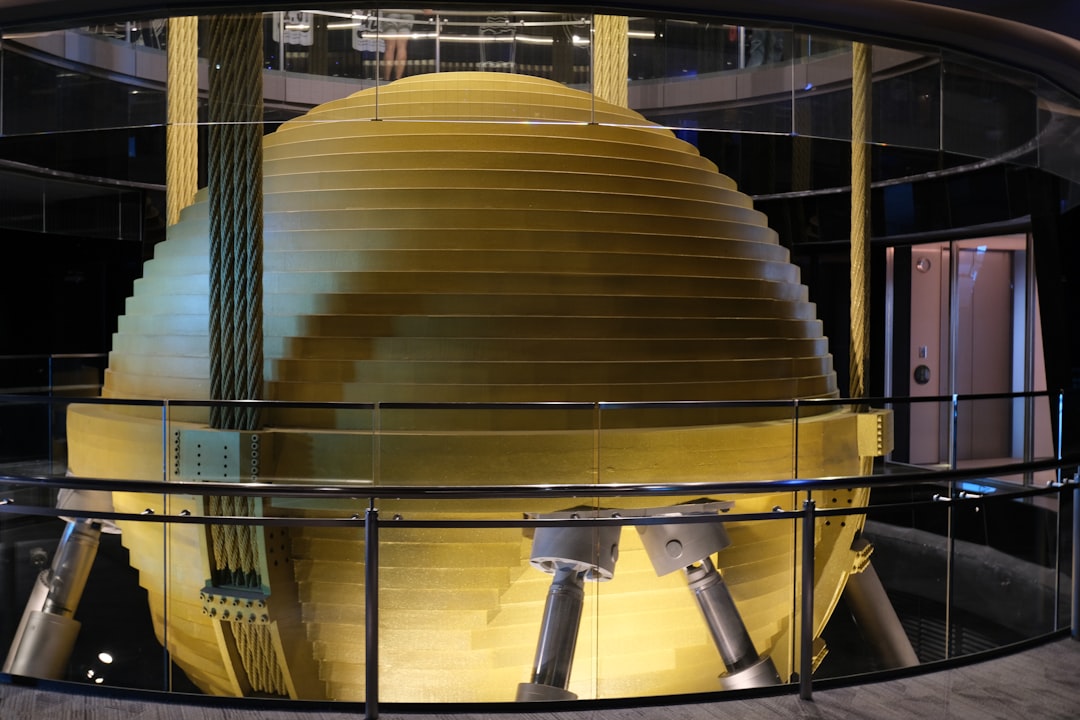

The approach is called an Accelerator-Driven System (ADS). Here's how it works: high-energy protons are fired at a heavy metal target, typically liquid mercury. This triggers a process called spallation, which releases a shower of neutrons. Those neutrons then interact with long-lived radioactive isotopes in nuclear waste, transmuting them into shorter-lived or stable forms.

It's elegant physics. But — and this is a substantial "but" — scaling it from laboratory demonstrations to industrial deployment is notoriously difficult.

Rongli Geng, the lead researcher, is refreshingly candid about the challenges: "The challenge is to really translate the accelerator science from where we are right now in terms of technology readiness to where the technology needs to be."

The DOE's NEWTON program (Nuclear Energy Waste Transmutation Optimized Now) has committed $8.17 million to address two critical engineering bottlenecks.

First, cooling. Current systems require expensive custom cryogenic plants to keep superconducting cavities at extreme low temperatures. Jefferson Lab is developing niobium-tin coated cavities that operate at higher temperatures, making it possible to use standard commercial cooling units instead. That's a meaningful cost reduction if it works at scale.

Second, power. The system needs a precise 10 megawatts of radio frequency energy at exactly 805 megahertz. The team is adapting magnetrons — yes, the components inside microwave ovens — to deliver that power. It's an example of repurposing mature technology for a new application, which historically has been one of the more successful paths to commercialization.

The NEWTON program's stated goal is ambitious: recycle the entire U.S. commercial nuclear fuel stockpile within 30 years. Industry partners including RadiaBeam, General Atomics, and Stellant Systems are involved.

So, should we be excited? Cautiously, perhaps.

The physics is sound. Transmutation works. But many promising nuclear technologies have stumbled during scale-up. The economics need to make sense: building and operating these accelerators is expensive, and they'll compete with simply continuing to store waste in dry casks — which, while not elegant, is relatively cheap and proven.

There's also the question of public acceptance. Nuclear technology carries political baggage, regardless of technical merit.

What I find most interesting is that this represents a fundamentally different approach to the waste problem. Instead of hoping geology will keep waste isolated for 100,000 years — longer than human civilization has existed — we'd be actively reducing the hazard period to something within a few human lifetimes. That's a more honest stewardship position.

Whether it's economically viable at scale remains to be seen. But the research deserves serious attention.