Scientists at the University of Southern Denmark have discovered a previously unknown virus that infects gut bacteria — and it shows up significantly more often in patients with colorectal cancer.

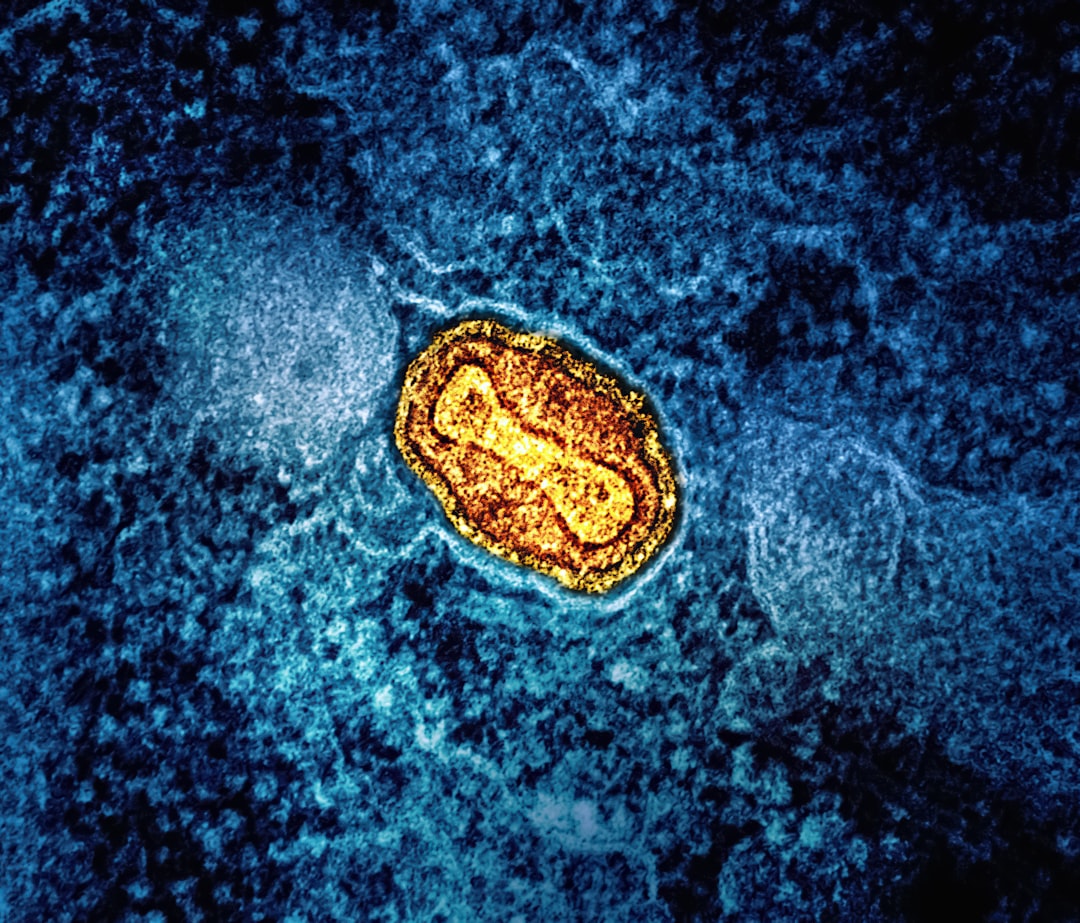

The virus is a bacteriophage, meaning it infects bacteria rather than human cells directly. In this case, it targets Bacteroides fragilis, one of the most common bacterial species in our intestines. After analyzing 877 individuals across Europe, the United States, and Asia, the researchers found that colorectal cancer patients were approximately twice as likely to harbor these specific viruses in their gut.

Now, before we jump to conclusions: this is correlation, not causation. The distinction matters enormously.

Flemming Damgaard, a medical doctor completing his PhD at the Department of Clinical Microbiology, is clear about the limitations: "We do not yet know whether the virus is a contributing cause, or whether it is simply a sign that something else in the gut has changed."

The discovery began somewhat serendipitously. The team was studying Danish patients who developed bloodstream infections from B. fragilis — a serious but rare complication. When they compared bacterial samples between cancer and non-cancer patients, the virus kept showing up in the cancer group.

That prompted the broader international validation study, published by the university, which confirmed the pattern holds across different populations.

The gut microbiome has emerged as one of the most active areas in cancer research over the past decade. We've learned that the trillions of microbes in our intestines don't just help digest food — they influence inflammation, immune function, and even how well cancer treatments work. Some bacteria produce metabolites that damage DNA. Others affect how our immune system surveils for tumor cells.

This virus adds another layer of complexity. Does it alter how B. fragilis behaves? Does it change which bacterial genes are active? Or is it simply a passenger, thriving in an environment that cancer has already altered?

Those are the questions Damgaard and his colleagues are now investigating through three follow-up projects. They're using artificial gut models, analyzing tumor tissue directly, and studying genetically predisposed mice to tease apart the virus-bacterium-tissue interactions.

One intriguing possibility: if the virus does contribute to cancer development, it could become a diagnostic marker. A simple stool test that detects the virus might flag high-risk patients earlier than current screening methods. That's speculative at this stage, but the statistical signal is strong enough to warrant serious investigation.

The universe doesn't care what we believe. Let's find out what's actually true. And in this case, figuring out whether this virus is a villain, a bystander, or something more nuanced could reshape how we understand one of the world's most common cancers.